News

In Depth: Celebrating 25 years of Wiggle

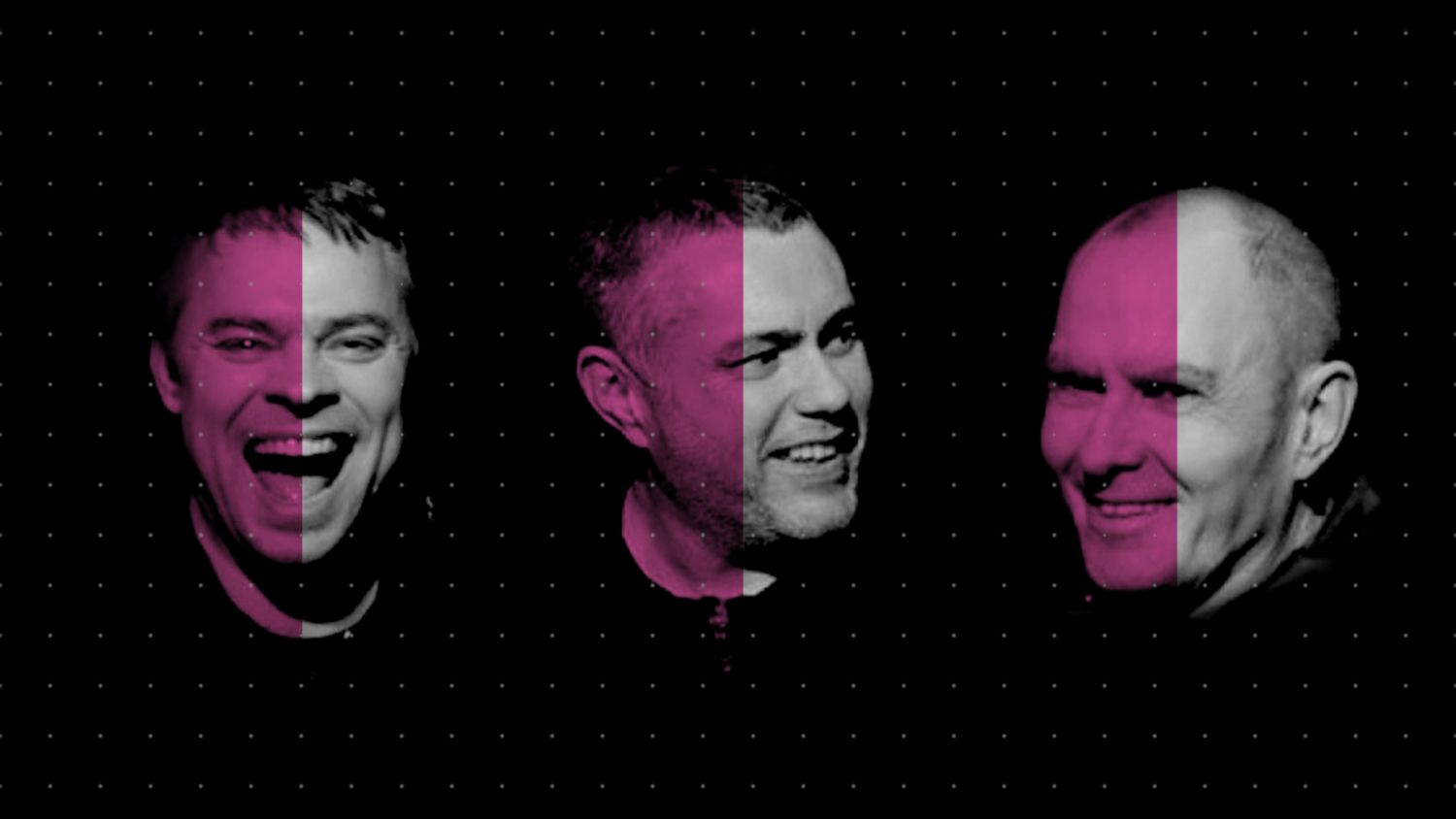

Saturday nights in Farringdon wouldn’t be the same without Wiggle. A few years before we’d even opened our doors, Terry Francis, Nathan Coles and Evil Eddie Richards were inspiring us, spearheading a new sound that defined London’s underground scene. While other mainstream clubs were playing more accessible derivatives of house, the trio were pioneering a style of dance music that married bass-heavy 4/4 with a slick house groove. This new sound – dubbed ‘tech house’ – became a movement, and Wiggle its key flagbearers. It quickly formed part of our story. Francis famously became a mainstay of our space from the beginning, and the full crew would regularly touch down for their own Wiggle showcases. They’ve remained influential both on us and the wider electronic music sphere, something they’re currently reflecting on with a new compilation and series of gigs in celebration of their 25th anniversary. Part of the festivities include an EC1 takeover this weekend, where Layo & Bushwacka! are set to join them in Room One. As we prepare to welcome them back to the space, we caught up with Francis, Coles and Richards to hear more about how it all started back in the mid-90s, defining ‘tech house’, and why they’re currently revisiting their illustrious back catalogue, one repress at a time.

Francis grew up in Leatherhead, Surrey. Based just outside the London Orbital, he would regularly travel into town for parties as a teenager, immersing himself in the scene during a heyday for Camden nightlife. “When I was 15 or 16, me and a mate of mine used to travel up to Dingwalls or High On Hope to see people like Norman Jay, and we’d hang out around Camden Lock,” he recalls. Within a couple of years a friend had shown him a few house records in his collection, and his love affair with club music started. Francis grew up listening to soul and funk artists like Loose Ends and Gwen Guthrie, but once his then girlfriend Claire took him to his first rave, the seeds of his future endeavours were sown. The pair would later marry, and, along with Coles’ long-term partner Louisa, she became instrumental to Wiggle’s early success. “The music was new, the people were new, the scene was new. Being a rebel, dancing outside, breaking the law, it was all just exciting,” Francis says.

Coles, meanwhile, was busy throwing parties across the city. His first one was a lowkey session called Face The Bass, located in a long-defunct photography studio on Old Kent Road. Coles threw Face The Bass in partnership with Justin Bailey, a close friend who would later put his hand to tracks together with the crew as part of Housey Doingz. One of the party’s key guests was Mr. C, who insisted on working with Coles on a new event called Release. Release brought together all of the scene’s key players, with people like Kid Batchelor, Colin Faver, Femi B, Laggy and Evil Eddie Richards among the guests. One night, Moby came to perform live. Mr. C later found mainstream success with The Shamen, which meant he had less time to organise the Release sessions. Coles then founded Release The Pressure alongside Gary Dillion, filling in on the decks for the first time in between their invited guests.

Eventually Coles invited Francis to play his Heart and Soul event. With the London climate becoming an increasingly strained environment for underground music, they hatched a plan to launch Wiggle. “Not many people were putting on underground house dos, or techno and house together, it was more handbaggy and Kiss FM whitewashed,” Francis says. The market had become more mainstream, people were only interested in bigger names, and promoters were avoiding taking risks. While the spirit of the acid house movement was still alive, the scene had become unrecognisable.

The first Wiggle party was meant to take place in a penthouse overlooking the Thames, but when the surrounding roads being closed for the London Marathon a matter of hours before doors opened, Coles and Francis were left scrambling to find a new venue. Following several frantic hours on the phone, Coles sourced a lock-up garage in Camden. They quickly emptied the garage, replacing spare car parts with their own sound rig. “It wasn’t a great start, but it certainly turned out alright in the end,” jokes Francis.

Saturday nights in Farringdon wouldn’t be the same without Wiggle. A few years before we’d even opened our doors, Terry Francis, Nathan Coles and Evil Eddie Richards were inspiring us, spearheading a new sound that defined London’s underground scene. While other mainstream clubs were playing more accessible derivatives of house, the trio were pioneering a style of dance music that married bass-heavy 4/4 with a slick house groove. This new sound – dubbed ‘tech house’ – became a movement, and Wiggle its key flagbearers. It quickly formed part of our story. Francis famously became a mainstay of our space from the beginning, and the full crew would regularly touch down for their own Wiggle showcases. They’ve remained influential both on us and the wider electronic music sphere, something they’re currently reflecting on with a new compilation and series of gigs in celebration of their 25th anniversary. Part of the festivities include an EC1 takeover this weekend, where Layo & Bushwacka! are set to join them in Room One. As we prepare to welcome them back to the space, we caught up with Francis, Coles and Richards to hear more about how it all started back in the mid-90s, defining ‘tech house’, and why they’re currently revisiting their illustrious back catalogue, one repress at a time.

Francis grew up in Leatherhead, Surrey. Based just outside the London Orbital, he would regularly travel into town for parties as a teenager, immersing himself in the scene during a heyday for Camden nightlife. “When I was 15 or 16, me and a mate of mine used to travel up to Dingwalls or High On Hope to see people like Norman Jay, and we’d hang out around Camden Lock,” he recalls. Within a couple of years a friend had shown him a few house records in his collection, and his love affair with club music started. Francis grew up listening to soul and funk artists like Loose Ends and Gwen Guthrie, but once his then girlfriend Claire took him to his first rave, the seeds of his future endeavours were sown. The pair would later marry, and, along with Coles’ long-term partner Louisa, she became instrumental to Wiggle’s early success. “The music was new, the people were new, the scene was new. Being a rebel, dancing outside, breaking the law, it was all just exciting,” Francis says.

Coles, meanwhile, was busy throwing parties across the city. His first one was a lowkey session called Face The Bass, located in a long-defunct photography studio on Old Kent Road. Coles threw Face The Bass in partnership with Justin Bailey, a close friend who would later put his hand to tracks together with the crew as part of Housey Doingz. One of the party’s key guests was Mr. C, who insisted on working with Coles on a new event called Release. Release brought together all of the scene’s key players, with people like Kid Batchelor, Colin Faver, Femi B, Laggy and Evil Eddie Richards among the guests. One night, Moby came to perform live. Mr. C later found mainstream success with The Shamen, which meant he had less time to organise the Release sessions. Coles then founded Release The Pressure alongside Gary Dillion, filling in on the decks for the first time in between their invited guests.

Eventually Coles invited Francis to play his Heart and Soul event. With the London climate becoming an increasingly strained environment for underground music, they hatched a plan to launch Wiggle. “Not many people were putting on underground house dos, or techno and house together, it was more handbaggy and Kiss FM whitewashed,” Francis says. The market had become more mainstream, people were only interested in bigger names, and promoters were avoiding taking risks. While the spirit of the acid house movement was still alive, the scene had become unrecognisable.

The first Wiggle party was meant to take place in a penthouse overlooking the Thames, but when the surrounding roads being closed for the London Marathon a matter of hours before doors opened, Coles and Francis were left scrambling to find a new venue. Following several frantic hours on the phone, Coles sourced a lock-up garage in Camden. They quickly emptied the garage, replacing spare car parts with their own sound rig. “It wasn’t a great start, but it certainly turned out alright in the end,” jokes Francis.

“To me it was more of an attitude – I didn’t like the term at first.”Francis and Coles packed their bags with house and techno, and photography was strictly forbidden. Any press requests were quickly denied. The first party saw Coles and Francis playing together alongside a small crew of friends. They invited Eddie Richards to play the second edition, who, in between running the booking agency Dy-Na-Mix, was already an established name playing regular gigs at places like Camden Palace and Haçienda. He was also a familiar face at Club 414, a recently-closed Brixton bar that would become a regular Wiggle hangout, but after a memorable debut, Coles and Francis invited him to enter the fold as a resident. Coles, Francis and Richards threw several more parties in random locations around London. Every event started to attract a bigger audience, and after a particularly busy night where people rammed into the space’s staircase leading into the dancefloor, they realised they’d outgrown intimate venues. Francis recalls: “We moved on, and started to do more warehouse parties. We just found random places. We did a party in a car auction house, a car park, all over really. Wherever we could get away with it. Nathan was the one who would chat to the police if they showed up. He told them it was a private party, and we weren’t selling the alcohol. We had to pretend that we were giving away the alcohol and that no money was changing hands at the bar. Even our crowd knew that if they were stopped outside and asked if we were selling alcohol, to say they got it for free. We couldn’t really get shut down. They could have done if they really wanted, but Nathan’s got a silver tongue, so we would always send him out to charm them. It really worked, and everyone had their part to play.” In between all of the Wiggle parties, Francis was holding down a job at Swag Records. Located in Croydon, it was the epicentre for the emerging tech house sound Wiggle were championing, stocking records from labels like Pagan, Surreal and Eukahouse. The shop was even responsible for coining the term ‘tech house’. For them it was an easy way to classify this new style, and anything that fused the swing of house with punchy techno fell under the umbrella. Francis worked at Swag for nine years, becoming a known face behind the counter alongside store owner Liz Edwards. “Tech house was just an abbreviation used at Swag Records to make it easier for people to ask for this music. To me it was more of an attitude – I didn’t like the term at first,” Francis explains. Richards is succinct in describing Wiggle’s signature sound: “It’s a rolling bassline groove, with elements of both house and techno”.

“Hiring unusual venues, avoiding advertising, building a following through word of mouth, and always investing in a good quality sound system.”Similar things were going on elsewhere across the UK. Leeds had Back to Basics, while Brighton was the home of Positive Sound, where ravers would dance on the beach in front of a custom-made white sound system. The sound was expanding. Richards started bringing people like Derrick May over to the UK, while Francis would regularly travel out to play on the east and west coasts of the USA. By 1999, we were prepping to open. Our founder Keith Reilly caught Francis playing at Soundshaft, and was so impressed he invited him to join our ranks the same night. Wiggle was still offering something different to most other parties across the capital. “There weren’t many club nights for that sound, so that’s where we made the biggest impact, as an outlet for that sort of music.” Francis helped guide the sound of our Saturday nights alongside Craig Richards, and, two decades deep into the story, he remains one of the cornerstones of our musical identity. While the parties were where tech house picked up steam, there were a number of labels helping to spread the sound. Eye 4 Sound, Surreal, End Recordings and Plank all helped fly the flag for the sound Wiggle had pioneered, and the trio would frequently play their records. Richards remembers carving out their own sound with a number of likeminded international labels. “We played tracks from labels such as Touché in Holland, DNH from Canada, Sex Mania from USA, and R&S from Belgium. They would all fit together and work in the mix. Other DJs around the world were probably doing the same, but it wasn’t just the track selection or mixing style that made it special in the UK. It was the way Wiggle presented the movement. Hiring unusual venues, avoiding advertising, building a following through word of mouth, and always investing in a good quality sound system.” With increased demand for the older Wiggle stuff today, the process of repressing a few of those early records has begun, both through the Wiggle Classics series, and with the help of labels like Holding Hands and Mint Condition. Coles is clear on the crew’s plans for the future: “Keep on keeping on with the label and the parties, doing what we love best.”

Tags

No items found.

.jpg)